![[Previous]](prev.gif) |

![[Contents]](contents.gif) |

![[Index]](keyword_index.gif) |

![[Next]](next.gif) |

![[Previous]](prev.gif) |

![[Contents]](contents.gif) |

![[Index]](keyword_index.gif) |

![[Next]](next.gif) |

This chapter includes:

In order for an application to produce sound, the system must have:

This whole system is referred to as the QNX Sound Architecture (QSA). QSA has a rich heritage and owes a large part of its design to version 0.5.2 of the Advanced Linux Sound Architecture (ALSA), but as both systems continued to develop and expand, direct compatibility between the two was lost.

This document concentrates on defining the API and providing examples of how to use it. But before defining the API calls themselves, you need a little background on the architecture itself. For those who want to jump in right away, full source for examples of a “wav” player and “wav” recorder are included in the appendix.

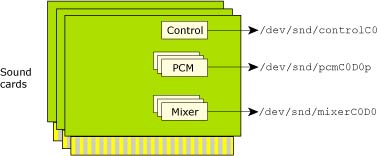

The basic piece of hardware needed to produce or capture (i.e. record) sound is an audio chip or sound card, referred to simply as a card. QSA can support more than one card at a time, and can even mount and unmount cards “on the fly” (more about this later). All the sound devices are attached to a card, so in order to reach a device, you must first know what card it's attached to.

Cards and devices.

The devices include:

You can list the devices that are on your system by typing:

ls /dev/snd

The resulting list includes one control device for every sound card, starting from card 0, as well as the PCM and mixer devices for each card.

There's one control device for each sound card in the system. This device is special because it doesn't directly control any real hardware. It's a concentration point for information about its card and the other devices attached to its card. The primary information kept by the control device includes the type and number of additional devices attached to the card.

Mixer devices are responsible for combining or mixing the various analog signals on the sound card. A mixer may also provide a series of controls for selecting which signals are mixed and how they're mixed together, adjusting the gain or attenuation of signals, and/or the muting of signals.

For more information, see the Mixer Architecture chapter.

PCM devices are responsible for converting digital sound sequences to analog waveforms, or analog waveforms to digital sound sequences.

Each device operates only in one mode or the other. If it converts digital to analog, it's a playback channel device; if it converts analog to digital, it's a capture channel device.

The attributes of PCM devices include:

The maximum number of subchannels supported is a hardware limitation. On single-subchannel cards, this limitation is artificially surpassed through a software solution: the software subchannel mixer. This allows 8 software subchannels to exist on top of the single hardware subchannel.

The number of subchannels that a device advertises as supporting is defined for the best-case scenario; in the real world, the device might support fewer. For example, a device might support 32 simultaneous clients if they all run at 48 kHz, but might support only 8 clients if the rate is 44.1 kHz. In this case, the device advertises 32 subchannels.

The QNX Sound Architecture supports a variety of data formats. The <asound.h> header file defines two sets of constants for the data formats. The two sets are related (and easily converted between) but serve different purposes:

Generally, the SND_PCM_FMT_* constants are used to convey information about raw potential, and the SND_PCM_SFMT_* constants are used to select and report a specific configuration.

You can build a format from its width and other attributes, by calling snd_pcm_build_linear_format().

You can use these functions to check the characteristics of a format:

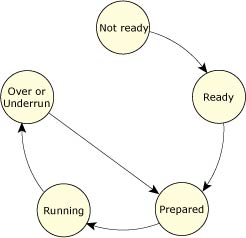

A PCM device is, at its simplest, a data buffer that's converted, one sample at a time, by either a Digital Analog Converter (DAC) or an Analog Digital Converter (ADC), depending on direction. This simple idea becomes a little more complicated in QSA because of the concept that the PCM subchannel is in a state at any given moment. These states are defined as follows:

General state diagram for PCM devices.

The transition between states is the result of executing an API call, or the result of conditions that occur in the hardware. For more details, see the Playing and Capturing Audio Data chapter.

In the case where the sound card has a playback PCM device with only one subchannel, the device driver writer can choose to include a PCM software mixing device. This device simply appears as a new PCM playback device that supports many subchannels, but it has a few differences from a true hardware device:

The PCM software mixer is specifically attached to a single hardware PCM device. This one-to-one mapping allows for an API call to identify the PCM software-mixing device associated with its hardware device.

In some cases, an application has data in one form, and the PCM device is capable of accepting data only in another format. Clearly this won't work unless something is done. The application — like some MPG decoders — could reformat its data “on the fly” to a format that the device accepts. Alternatively, the application can ask QSA to do the conversion for it.

The conversation is accomplished by invoking a series of plugin converters, each capable of doing a very specific job. As an example, the rate converter converts a stream from one sampling frequency to another. There are plugin converters for bit conversions (8-to-16-bit, etc.), endian conversion (little endian to big endian and vice versa), channel conversions (stereo to mono, etc.) and so on.

The minimum number of converters is invoked to translate the input format to the output format so as to minimize CPU usage. An application signals its willingness to use the plugin converter interface by using the PCM plugin API functions. These API functions all have plugin in their names. For more information, see the Audio Library chapter.

|

Don't mix the plugin API functions with the nonplugin functions. |

![[Previous]](prev.gif) |

![[Contents]](contents.gif) |

![[Index]](keyword_index.gif) |

![[Next]](next.gif) |